Most of the major buildings on Kalamazoo College’s campus are served by a central cooling plant. Campus-wide cooling systems are not like your residential air conditioner in either scale or process. Because the cooling liquid must travel from the chiller plant at the far east end of campus, to all the buildings served, including those up hill at the west end of campus, the chilled water must be very cold when it leaves the plant. When it reaches each building, typically it flows through a coil in an air handler where the supply air flows over it cooling the air. It also flows over a coil with heated liquid that helps temper the air to create the desired indoor climate. If there is no re-heat available, the ability to control the temperature of the discharge air is severely hampered.

Why does K use this kind of a system?

Simply put, this type of system is far more energy efficient than cooling spaces with a residential style air conditioner. They also last longer and require less maintenance. The largest air conditioner units can cool about 3,000 square feet maximum. Just imagine the 100’s of individual air conditioners dotted all around campus, with a life-span of about 10 years, that would require a team of several technicians to keep them operational and replace them regularly. Indeed, a commercial system cannot be started as quickly as flipping a switch at home, and it requires re-heat to operate properly, but the cost savings are tremendous; in energy, labor, equipment and uptime, not to mention aesthetics.

So why is the steam off?

The Campus’ Central Steam Plant is currently out of operation to make repairs to branch lines that serve Trowbridge, Dewaters and Stetson Chapel. At the heart of the problem is the age of the system. While K’s central plant may have been installed in the early 1960’s, the campus buildings were served by municipal steam prior, so some of the components of the distribution system are from the 1930’s. Steam is distributed through the campus in a loop. Where steam is delivered to buildings and circulated through heat exchangers, the condensate is returned to the steam plant through paralleled lines. Carbon dioxide is formed in steam from the thermal breakdown of the carbonate alkalinity naturally present in make-up water, and when it mixes with the condensate it forms carbonic acid. This acid eats away at the components of the system over time, and while there are modern industrial chemical additives that help mitigate this, for much of the systems life they were not in use.

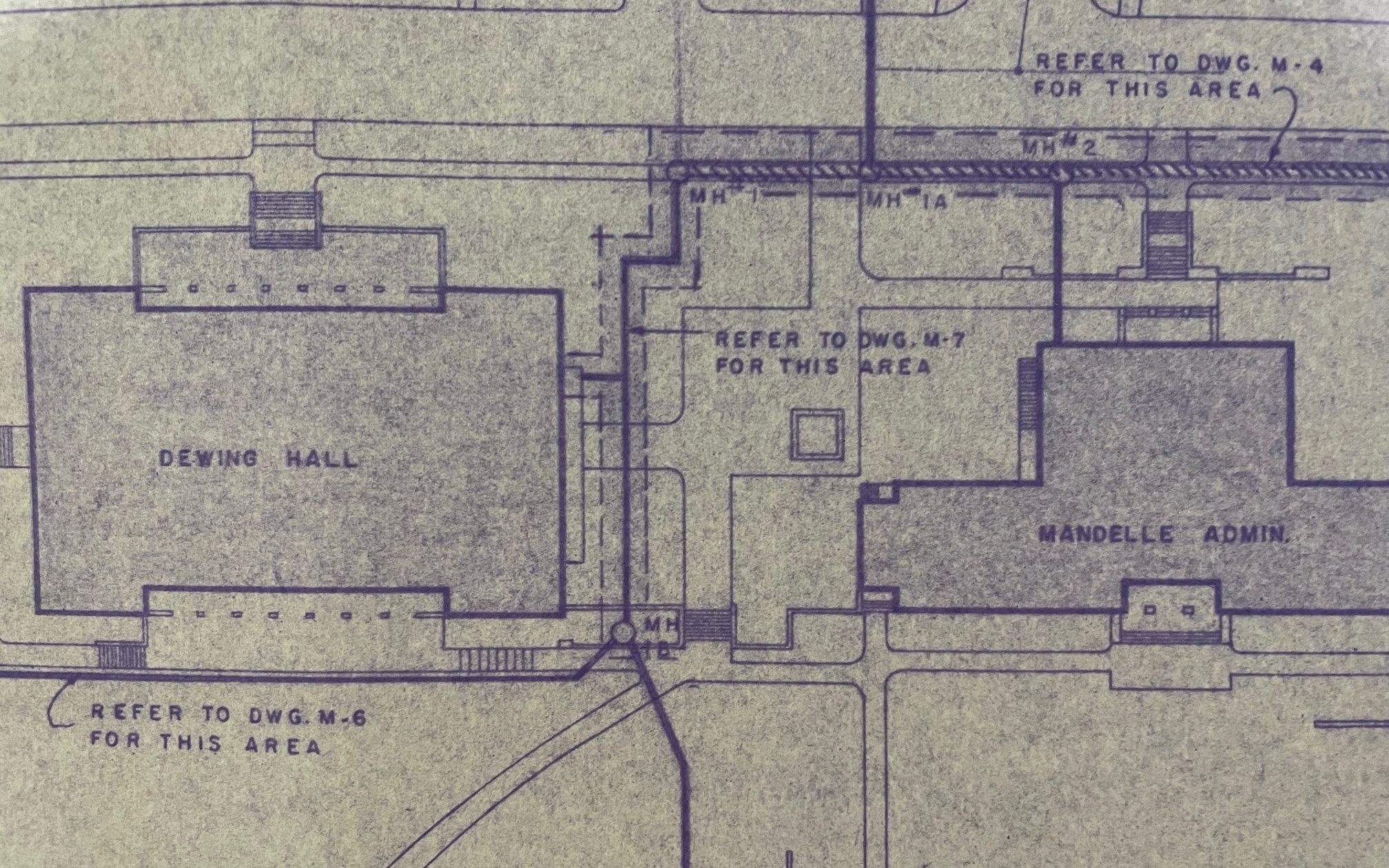

The present issue is within a steam vault at the south side of red square, which is simply so deteriorated from carbonic acid attack that it needs to be re-built, replacing all the mechanicals and stabilizing the vault where the concrete itself has been attacked. This includes valves that might have allowed the team to isolate part of the system, hence the entire system needs to be out of service. In order to replace the piping, the team must work backwards from the vault until they find piping solid enough to connect with the new pipe. Since this requires excavation to find good pipe, it is difficult to establish a time-line when the repairs will be complete, because the extent of the problem is unknown. The mechanical work taking place in the vault is made more difficult by the safety concerns of working in a confined space, which requires oxygen monitoring and emergency worker retrieval systems.

What is the plan for our aging steam system?

There is one, a good one, but that is for another post.

We know none of this makes your cold work spaces any more comfortable, but we do hope understanding how complex the repair is will make you feel a little better about bringing your sweaters out of hibernation for a few weeks.